Dr. Manzur Ejaz

In India & Pakistan, a fundamental change of ancient agrarian system through mechanisation and commercialism created an ideological vacuum, which was filled by the religious parties. It is naïve to base analysis on the basic notion of Islam and Hinduism: the political version of both is similar if not identical

Whenever any reference is made to India, my inbox sees a barrage of criticism by Indian readers. Thus, I find one question should be answered once and for all: is it legitimate to compare one society with another and what would be the common denominators that make the comparison really genuine?

I think most scientists would agree that comparative studies are useful to derive universal laws to describe human and non-human behaviour. However, people, uninitiated in the basis of social sciences, start with an unsustainable assumption that human societies have no common denominator. In reality, all the ‘isms’ — capitalism, Marxism, pragmatism — believed or practiced, are based on the assumption that there are common denominators. For example, common history and socio-political evolution can be used as a denominator for description or prescription.

Most Pakistanis and Indians equate Pakistan with the Muslim world and start idealising or criticising it, as if religion is the single most important denominator.

Whenever any reference is made to India, my inbox sees a barrage of criticism by Indian readers. Thus, I find one question should be answered once and for all: is it legitimate to compare one society with another and what would be the common denominators that make the comparison really genuine?

I think most scientists would agree that comparative studies are useful to derive universal laws to describe human and non-human behaviour. However, people, uninitiated in the basis of social sciences, start with an unsustainable assumption that human societies have no common denominator. In reality, all the ‘isms’ — capitalism, Marxism, pragmatism — believed or practiced, are based on the assumption that there are common denominators. For example, common history and socio-political evolution can be used as a denominator for description or prescription.

Most Pakistanis and Indians equate Pakistan with the Muslim world and start idealising or criticising it, as if religion is the single most important denominator.

Pakistanis project themselves to be part of the so-called ummah in self-denial of their own real history to idealise their past and Indians find it convenient to put Pakistan in a religious category and demonise it.

Pakistanis believe they are heirs of Muslim rule and their opponents believe in the same notion as well. In short, Pakistani and Indian nationalists agree on this point.

The fact of the matter is that most of the Muslims living in Pakistan are converts of lower layers of different castes. Till the time of the partition their status as a lowly mass of peasants, artisans and labourers continued. Muslim feudal lords mostly owned land and urban centres were completely run by the Hindu elite.,Muslims of the present Pakistan had hardly any representation in the business community, bureaucracy, or education.

The fact of the matter is that most of the Muslims living in Pakistan are converts of lower layers of different castes. Till the time of the partition their status as a lowly mass of peasants, artisans and labourers continued. Muslim feudal lords mostly owned land and urban centres were completely run by the Hindu elite.,Muslims of the present Pakistan had hardly any representation in the business community, bureaucracy, or education.

During the entire Muslim rule, their status remained similar to the untouchables who converted to Christianity during the British rule. Therefore, other than a small percentage of Urdu speakers who may have come from the old ruling Muslim elite, it is misleading for the Pakistanis to idealise themselves as heirs to Muslim ruling elites who had descended from Central Asia, Afghanistan, Iran and the Middle East.

Looking at the National Assembly members, representatives of the people of Pakistan, there will be hardly anyone from traditional rulers of Muslim India like the Mughals, Ghauris, Ghaznavis, Khiljis or Lodhis. Most of the National Assembly members have been and are Jats, Rajputs, Gujjar, Arain and Syed. The caste make-up of the ruling classes in Pakistan, the majority of whom come from Punjab and Sindh, is similar to contemporary northern Indian states if one equates the status of Syeds with Brahmins.

Looking at the National Assembly members, representatives of the people of Pakistan, there will be hardly anyone from traditional rulers of Muslim India like the Mughals, Ghauris, Ghaznavis, Khiljis or Lodhis. Most of the National Assembly members have been and are Jats, Rajputs, Gujjar, Arain and Syed. The caste make-up of the ruling classes in Pakistan, the majority of whom come from Punjab and Sindh, is similar to contemporary northern Indian states if one equates the status of Syeds with Brahmins.

Conversions of Jat, Rajput or Gujjar families have made no difference to their day-to-day behaviour and the caste system is alive and well in both India and Pakistan. If one looks at the last names in Punjab one can find their exact counterparts in India, specifically among the dominating Jats. If Alberuni would come to his India today — it was only Punjab because he accompanied Mahmood Ghaznavi, who had conquered only this region — his differentiation of Indians from northern invaders would not be different.

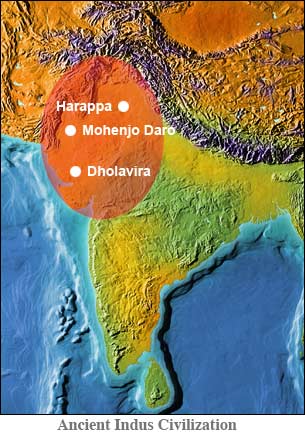

In short, despite the misleading idealisation by Pakistanis and demonisation by Indians, the majority of Pakistanis have their roots in the Indus Valley civilisation.

Their eating and drinking habits, marriage and death ceremonies are comparable to the people of northern India. Therefore, a large part of Pakistan and northern India can be rightfully compared even if the Indian counterparts fare better than Pakistan.

On the empirical level, there are intriguing parallels. For example, an extremist religious uprising first emerged in Indian Punjab in the form of the Khalistan movement. To start with, the ruling party in Indian Punjab, Akali Dal, has been much more religious than its counterparts in Pakistan. One can blame Indira Gandhi or Ziaul Haq for creating and abetting the Khalistan movement, but the fact remains that outsiders can only exploit the potential and cannot create a large-scale conflict from nowhere. Therefore, the Khalistan movement was a precursor of religious extremism in northern India.

The rise of various extremist religious and sectarian outfits in Pakistan during the 1980s coincides with the emergence of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), an offshoot of the extremist Hindu ideological formation, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS).

On the empirical level, there are intriguing parallels. For example, an extremist religious uprising first emerged in Indian Punjab in the form of the Khalistan movement. To start with, the ruling party in Indian Punjab, Akali Dal, has been much more religious than its counterparts in Pakistan. One can blame Indira Gandhi or Ziaul Haq for creating and abetting the Khalistan movement, but the fact remains that outsiders can only exploit the potential and cannot create a large-scale conflict from nowhere. Therefore, the Khalistan movement was a precursor of religious extremism in northern India.

The rise of various extremist religious and sectarian outfits in Pakistan during the 1980s coincides with the emergence of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), an offshoot of the extremist Hindu ideological formation, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS).

The BJP’s predecessor, the Bharatiya Jana Sangh, was formed in 1951 by the RSS but it did not take off. It was during the 80s — the BJP was formed in 1980 — that a political party with political Hinduism gained significance. The BJP gained momentum in 1984 for protesting the massacre of 10,000 to 17,000 Sikhs in Delhi. This was the time when the US and the Pakistan army were creating and grooming private jihadi militias to fight the Soviets in Afghanistan.

However, the fundamental reason for the simultaneous emergence of extremist religious groupings in Pakistan, the Khalistan movement and the Saffron revolution can be traced to a rapid change of the political economy of the entire northern India — including Pakistan. A fundamental change of ancient agrarian system through mechanisation and commercialism had created an ideological vacuum, which was filled by the religious parties. A new ideology of political Islam, Hinduism and Sikhism was born. It is naïve to base analysis on the basic notion of Islam and Hinduism: the political version of both is similar if not identical.

However, if one starts with an extremist individualist approach, no state or province within India and Pakistan can be compared to each other. How can we compare Pakistani Punjab with Balochistan or East Punjab with Orissa or Kerala? But if historical commonality is taken to be a common denominator then the northern parts of the subcontinent can be analysed as a single phenomenon. Most of the northern Indian states were centres of or offshoots of the Indus civilisation. The languages spoken in this area have more than 70 percent common vocabulary.

However, the fundamental reason for the simultaneous emergence of extremist religious groupings in Pakistan, the Khalistan movement and the Saffron revolution can be traced to a rapid change of the political economy of the entire northern India — including Pakistan. A fundamental change of ancient agrarian system through mechanisation and commercialism had created an ideological vacuum, which was filled by the religious parties. A new ideology of political Islam, Hinduism and Sikhism was born. It is naïve to base analysis on the basic notion of Islam and Hinduism: the political version of both is similar if not identical.

However, if one starts with an extremist individualist approach, no state or province within India and Pakistan can be compared to each other. How can we compare Pakistani Punjab with Balochistan or East Punjab with Orissa or Kerala? But if historical commonality is taken to be a common denominator then the northern parts of the subcontinent can be analysed as a single phenomenon. Most of the northern Indian states were centres of or offshoots of the Indus civilisation. The languages spoken in this area have more than 70 percent common vocabulary.

Sixty years of post-partition history cannot overturn the common history of thousands of years.

If today factors like corruption, nepotism, general lawlessness in society, unplanned growth, suicides and sectarian bickering are used as common denominators, Pakistani Punjab, Sindh and the northern Indian states will appear to be one contiguous area.

If today factors like corruption, nepotism, general lawlessness in society, unplanned growth, suicides and sectarian bickering are used as common denominators, Pakistani Punjab, Sindh and the northern Indian states will appear to be one contiguous area.

Travelling from Multan to Delhi by road shows that other than the difference of Sikh turban and beards, everything else is identical. There are sufficient common factors of history and centuries-old lifestyle that link these areas. Therefore, comparative studies of northern India and large parts of Pakistan are a genuine scholarly pursuit.

The writer can be reached at manzurejaz@yahoo.com

The writer can be reached at manzurejaz@yahoo.com

_____

Source:Wichaar.com

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are the sole responsibility of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the ‘Wonders of Pakistan’. The contents of this article too are the sole responsibility of the author(s). WoP will not be responsible or liable for any inaccurate or incorrect statements contained in this post.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are the sole responsibility of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the ‘Wonders of Pakistan’. The contents of this article too are the sole responsibility of the author(s). WoP will not be responsible or liable for any inaccurate or incorrect statements contained in this post.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are the sole responsibility of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the ‘Wonders of Pakistan’. The contents of this article too are the sole responsibility of the author(s). WoP will not be responsible or liable for any inaccurate or incorrect statements contained in this post.

YOUR COMMENT IS IMPORTANT

DO NOT UNDERESTIMATE THE POWER OF YOUR COMMENT

No comments:

Post a Comment